Within the United Kingdom we have a wide range of high hazard industries that undertake a variety of complex operations from production through to storage and distribution. Strong regulations, design standards and rigorous codes of practice rightly put the primary focus on safety within these plants, ensuring that systems and processes are carried out within safe operating environments, whilst providing controls should these be exceeded.

Yet, we can all think of names that are associated with the failure of these systems and processes:

- Flixborough 1974

- Bhopal 1984

- Piper Alpha 1988

- Buncefield 2005

- Gulf of Mexico 2010

As the HSE noted in the Introduction to its 2009 Final Report on Buncefield:

“The recent Texas City and Buncefield incidents have moved industry and regulators beyond the pure science and engineering responses to develop ways to prevent a recurrence. They have caused us to also critically examine the leadership issues associated with delivering what has to be excellent operation and maintenance of high-hazard processes.”

Later, on page 63, the report goes on to state:

“ … a culture of process safety should be actively developed, grown and championed from the top of an organisation. Industry should demonstrate a commitment to process safety leadership, and a willingness to promote the process safety agenda at all levels within an organisation, and externally with other stakeholders.”

What went wrong at Buncefield?

As the HSE report details: In the early hours of Sunday the 11th of December 2005, a number of explosions occurred at Buncefield Oil Storage Depot in Hertfordshire. At least one of the initial explosions was of massive proportions and there was a large fire, which engulfed much of the site.

Over 40 people were injured; fortunately there were no fatalities.

Significant damage occurred to both commercial and residential properties in the vicinity and a large area around the site was evacuated on emergency service advice.

The fire burned for several days, destroying most of the site and emitting clouds of black smoke into the atmosphere.

The HSE (Health and Safety Executive) and EA (Environment Agency) investigated the incident and secured convictions against five companies, who were ordered to pay almost £10m in combined fines and costs.” (HSE Buncefield Response)

Buncefield was an upper tier COMAH site and had a ‘robust’ set of systems in place to prevent, control and mitigate MAH (Major Accident Hazards). Yet, despite these systems, containment was lost and an ignition source found.

Reviewing the varying and wide ranging reports, we can see that a series of failings had been embedded over many years, and they had gone undetected; or, when they had been highlighted, they were not acted upon. Failures included:

If we look at what went wrong in even more detail, we realise that the fire was caused by several errors and oversights – few of which were disastrous in and of themselves, but all of which were critical and all of which contributed to a widespread systemic failure. Details matter!

We can divide these errors and oversights into two groups – Underlying and Root Causes. Specifically:

Underlying Causes for Buncefield:

❖ Control of incoming fuel. There was no access to the monitoring information on the main incoming lines, only from receipt tanks. Also, there was no immediate access to emergency shutdown.

❖ Fourfold increase in throughput. This led to increased driver numbers and to an increased level of overtime by staff. Poor shift handovers also led to confusion on operating tanks and pipelines.

❖ Tank filling procedure. Alarm levels were used inconsistently, meaning the product would be taken to ‘High’ or ‘Hi Hi’ levels. There was a reliance on the alarms to notify of level reached. There was no investigation into these, no additional safeguards and no reporting of such events. Essentially, there was no effective Safe System of Work!

❖ Inadequate fault logging. There was an inconsistent approach to problem solving – issues were often fixed ‘temporarily’. Additionally, there was poor handover and reporting of this (with no recognised and consistent Handover System). Staff were unaware of the reliability of safety critical equipment.

❖ Secondary Containment design issues. These included ‘Tie Bar penetrations’ and ‘pipeline penetrations’ and there was no suitable tertiary containment.

❖ Safety Management Systems, Managerial Oversight and Leadership The submitted safety report did not match what happened at site, lacking MoC (Management of Change) for changes to SCE (Safety Critical Elements). There was no checking that bunds were built to good practice, no bund maintenance regime, and bund failures were not treated as near misses!

Root Causes for Buncefield:

❖ Design of the Independent High Level Switch.

❖ Failure of the Level Switch (This had stuck on 14 different occasions and was not correctly rectified or logged).

❖ There was only one monitoring screen and tank displays were ‘stacked’, leaving the crucial Tank 912 at the back!

❖ Redundant Emergency Shutdown – The Mimic system on the screen to activate emergency shutdown was not active and not communicated to all operators.

❖ Newer versions of the gauge alarm system were fitted with an alarm that activates when there is a static gauge but moving product – these were not updated at Buncefield.

So, you see, no one factor was responsible for the explosion, save a general lack of due diligence at every level.

Health and Safety Regulation

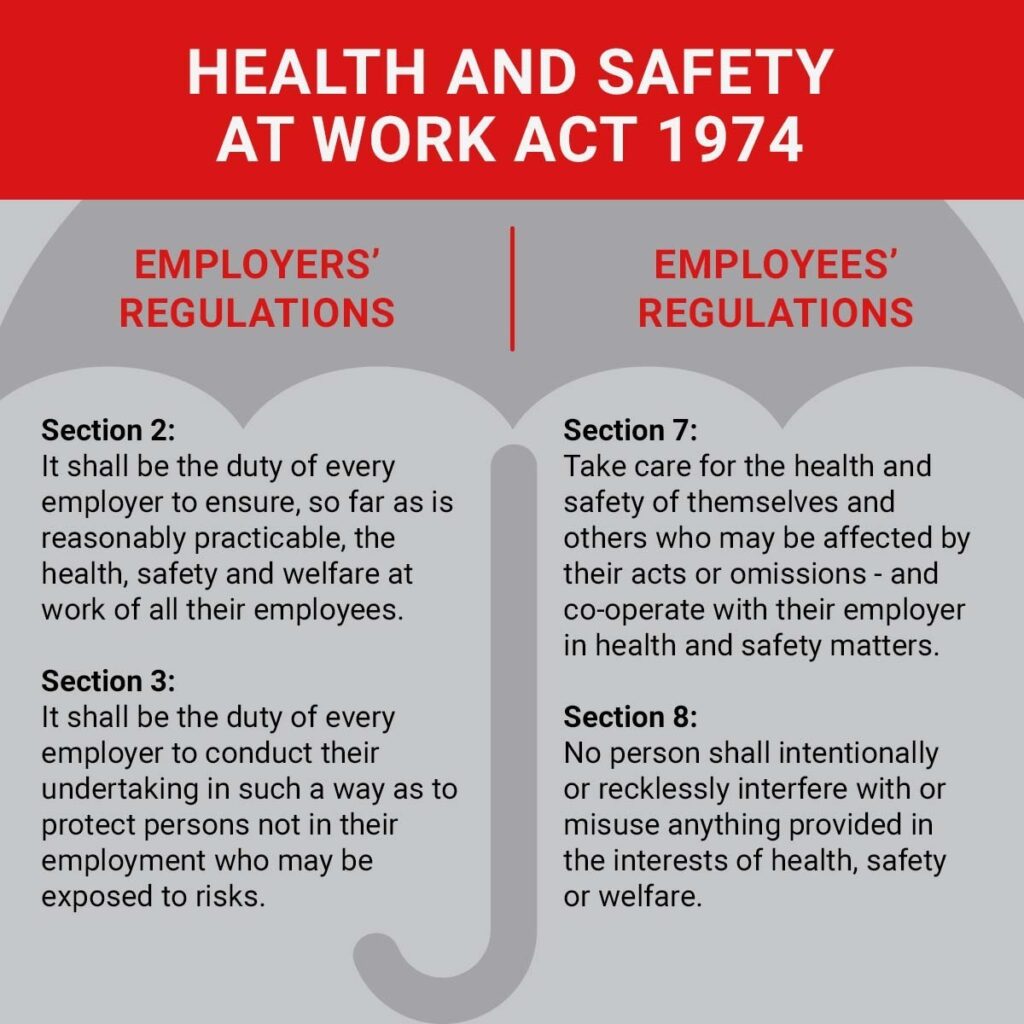

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 is the main legislation covering health and safety within the United Kingdom. It is an ‘umbrella’ Act which places specific duties on employers and employees, whilst underpinning core regulations providing a robust set of laws that must be adhered to.

Before the introduction of this Act, health and safety was often dealt with in a reactive way, meaning that legislation was created to prevent an accident happening again, rather than to reduce the chances of it happening in the first place.

The 1974 Act also saw the creation of the Health and Safety Commission and, later, the Health and Safety Executive (the two bodies eventually merged, in 2008).

Prior to 1974, there were different regulations for different industries, the new Act set out regulations and responsibilities that applied to all employers and all employees, irrespective of their industry.

The new proactive approach of the 1974 Act encouraged the involvement of the employees – the ones who actually do the work and use the equipment – in developing best health and safety practices, rather than dictating specifics from on high.

In this way, both the employees and employers took seriously their responsibilities for occupational health and safety.

It isn’t someone else’s responsibility to ensure that you are working in a healthy and safe way. By the same token, it isn’t only your responsibility to ensure that you have received correct training and that your equipment is fit for purpose. Everyone in the workplace is a stakeholder in everyone’s health and safety.

This is clearly what failed at Buncefield – there wasn’t sufficient competence and diligence to notice where systems and equipment were failing or were likely to fail.

Introducing Process Safety Management (PSM)

The way of combating all of this, in an attempt to proactively attempt to prevent accidents of any nature happening, is the development of the principles of Process Safety Management (PSM).

A useful definition of Process Safety, as published by The Energy Institute in 2016, is:

“Process safety is a blend of engineering and management skills focused on preventing catastrophic accidents and near misses, particularly structural collapse, explosions, fires and toxic releases associated with loss of containment of energy or dangerous substances such as chemicals and petroleum products. These engineering and management skills exceed those required for managing workplace safety.”

The two areas of focus for this are:

Occupational Safety: This concerns how we, as individuals, stay safe and prevent injury to ourselves and each other. Typically, incidents of this type have a high likelihood but a low consequence to the business as a whole – although, the consequence to the people involved may be significant.

Process Safety: This is based around the production and processing activities that have the potential to cause widespread damage and injury to the business, the surrounding area and the environment. Incidents of this type are, thankfully, of low likelihood but extremely high consequence.

Clear management structures and leadership are critical in maintaining both of these elements. Within Process Safety we need vigilance at every stage of the journey, from the initial site design (long before the fuel and chemicals flow) through to decommissioning (long after the liquids have dried up).

Only this level of vigilance can ensure safety is maintained, throughout.

To ensure the effectiveness of this (as much as is possible) we need a systematic approach to monitoring and maintaining safety in the high hazard sector – and beyond.

We shall look at this in PSM Chapter 2 – The Major Hazard Regulatory Model, which will be available at the beginning of October.

Teaching Safety is a Matter of Course

The secret to maintaining good Process Safety – and it’s no secret, really – is ensuring that everyone on your site has had the training they need.

Our Intro into Process Plant Operations course is a great place to begin – offering learners valuable ‘hands on’ experience of safe plant procedures and plant familiarisation.

Our IOSH-approved Process Safety Awareness and Principles of Process Safety Management courses are the perfect way to ensure that everyone develops the competencies they need.

And, as we have seen, successful Management of Change is also crucial to the smooth and safe running of a facility. That’s why we also offer a course on the Principles and Practice of Management of Change.

So, why not check out our full range of courses and get in touch, today.